In the world of Indian cinema—where fantasy meets formula—few tropes have persisted as stubbornly as the tendency to pair aging male superstars with much younger female leads. What was once accepted without question is now being challenged more vocally—by audiences, actors, and filmmakers alike.From veteran performers to outspoken critics, many are beginning to interrogate not just the optics of these on-screen pairings, but the deep-seated ideology that fuels them. The verdict? Male stardom is still synonymous with timeless appeal, while female desirability is tightly shackled to youth.In this special feature, ETimes gathers unfiltered insights from industry insiders who lay bare the gendered dynamics of Indian cinema’s most controversial romantic formula.The classic formula: older male star, young female lead

Veteran actor Govind Namdev sums up the mindset behind this casting trend: “The audience will only like it if there is pairing. Otherwise, why would there be? The producer who invests so many crores, he invests it with the hope or with the observation that people like this pairing.”For decades, commercial logic has kept this formula alive—pairing a popular, aging male star with a young heroine is seen as a safe bet at the box office. Namdev explains, “Like Salman Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, Ajay Devgn — their heroines are always young. The public likes this pairing, and producers spend crores betting on it.”This idea of “audience preference” reflects more than just business sense—it reveals a societal mindset where men are expected to age gracefully, while a woman’s value is tightly tied to her youth.“Patriarchal, clichéd, and unrealistic”

Actress Shenaz Treasury offers a sharp critique of this trend: “Unrealistic. Patriarchal. Cliché. Unless the script actually acknowledges the age gap, I’m out. If they cast a 50+ woman opposite a 25-year-old man? Now that would be interesting. Let’s flip the script for once. But most times, they just pretend the man is ageless and the woman… invisible after 35. So unless the story has something real to say about that dynamic, I’m not buying it.”She points out how often the age difference is ignored in scripts, as if men don’t age and women simply vanish after 35. She says, “Sadly, yes. Aging is treated like a scandal. ‘OMG she’s 43!’ – they say it like it’s a crime. Not ‘Wow, she has so much life experience, depth, and power.’ We shame women for getting older, then wonder why everyone’s injecting fillers into their faces at 30. And the worst part? Talent doesn’t always save you. Wrinkles are still a bigger problem than weak scripts.”Treasury’s words highlight the double standard women face both on-screen and off—where appearance matters more than talent, and aging is treated like something shameful.The double standard: men age, women disappear

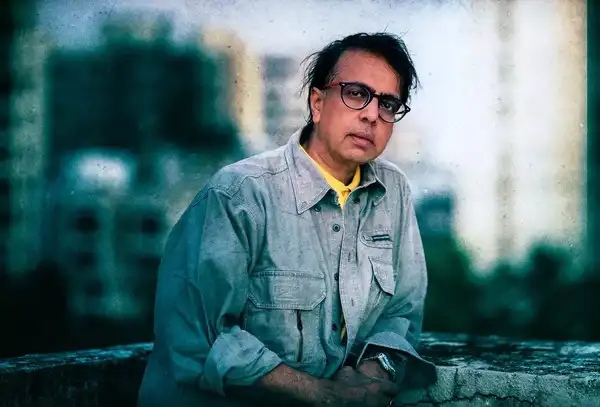

Filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri sums up the gender imbalance clearly: “When I started my career in 2005 with Chocolate, I realized that almost all actors, regardless of their age—whether 40, 50, 60, or 70—insist on having a younger heroine. In fact, there was a time when directors were pressured to sign only young actresses, and this is also a tradition in the South. If you look at South Indian cinema, no matter the hero’s age, the heroine has to be young, fair-looking, and sexy. So, what does this indicate? It basically indicates that the role of women in our films is only for three criteria: they have to be young, sexy and desirable. And it is considered that the desirable age is only when you are young and not married.”He points out how men’s aging is overlooked or even celebrated, while women’s careers drop off once they marry or grow older: “A hero can have five marriages, affairs, get as old as he wants, do VFX to his face, shoot with body doubles… nothing matters because we make hero worshipping films, not heroine worshipping ones.”Agnihotri’s words expose the patriarchal system that keeps male stars on a pedestal while women are pushed aside as they age. “No matter how talented an actress is or how good her performances are, once she gets married or is seen to be in a relationship with someone, her demand suddenly goes down,” he adds.Searching for new stories: actors want meaningful rolesGovind Namdev shares a more hopeful take based on changing audience tastes: “These days, people are liking biographies more. They are liking stories coming from real incidents… If people like my work, they want to see me in a new form.”He welcomes roles that allow for fresh, unconventional pairings: “If I am paired with a heroine, I will get to see something new… On screen, as a performance, we will get to see something new, there will be some new movements.”Namdev’s views suggest audiences are ready for stories that explore romance beyond youthful glamor—stories with older characters who bring emotional depth and authenticity.

Industry inertia slows changeDespite growing calls for more realistic and diverse storytelling, Bollywood’s old power structures keep progress slow. Agnihotri comments: “There are very few heroine-centric movies made in our industry. And even those are typically made when leading actresses get married, have children, retire, or reach an age where they can no longer be paired with a male hero—only then are they cast in such roles. This is a very male-dominated industry. It has been like this for umpteen number of years and I have a feeling it’s going to remain like this for a very long time.”He also reveals how star egos influence casting decisions: “Heroes also dictate on the set… if a heroine is taller, they will stand on stools or use tricks to appear taller themselves.”This shows how patriarchy controls not just stories, but the entire filmmaking process—reinforcing old norms.Agnihotri elaborates further: “Another problem is that the roles, the way they are conceived and written is only, only, only to boost the ego of the star, not of the character. We don’t write character-driven roles, we write star-driven roles. We want the star to be so happy with those, writing of those roles that he should say yes to the film then and there. And another problem is that heroes also dictate on the set, you know. Like a taller heroine, no, no, then heroes will get a patla and they will stand, which means a six-inch stool or three-inch stool and they’ll stand on that. So taller heroines generally have an issue over there. And in any scene if a heroine is dominating a lot, now this is a secret nobody wants to talk about, but in a scene where heroine is really dominating or her performance is better than the hero, then very often her performances will be trimmed or she may be speaking dialogues but the camera will stay on the close-up of the hero. This is a very, very common thing in commercial films. As far as I am concerned, I don’t make those kind of films, I make very, very realistic films, so I don’t see that problem. And in my film, all the heroines are very, very powerful, they don’t depend on the men at all. In fact, they challenge men. If you look at Buddha in a Traffic Jam, same case. If you look at The Tashkent Files, the main lead actress was a heroine who challenged the entire system. In that, the role of Pallavi, though she is handicapped on a wheelchair but a very powerful role. If you see The Kashmir Files, again you will find on one side there is a woman who is a victim but on the other side there is a woman who is challenging the system and changing the system. Yes, that was a kind of a negative role. If you look at it from one perspective, from another perspective, it’s a very, very powerful role. And same in the case of The Vaccine War. Vaccine War was about Indian women scientists and we celebrated them. Women scientists say, we can do it. And my next film, The Bengal Files, again has very, very, very strong women roles. In fact, I would call it a woman-centric film. So I don’t face that problem and I deliberately do that because that’s how I look at women.”Actress Sohaila Kapur sums it up with piercing clarity: “Simple answer. We are a society still stuck in patriarchy.”Reimagining romance: What the future could look likeShenaz Treasury believes it’s high time love stories reflect real life better. “Make a love story about people in their 40s or 50s — post-divorce. Or a woman in her 50s with a 38-year-old man. Now that would be more real and romantic.”When asked what desirability means for women on screen — and whether that definition is changing — Shenaz says, “Women also like looking at hot men. Period. So let’s stop pretending it’s only women who need to look good. When I was growing up, men could have paunches and still be romantic heroes. Now they’re hitting the gym too — and I’m thrilled about that.”On how patriarchy influences the way romance is written and visualized in Indian cinema, she doesn’t hold back: “So many rom-coms still feel like they were written by a 60-year-old uncle who thinks women don’t age and men don’t need therapy. The power dynamic is always tilted. Women have to be perfect. Men just have to show up. But times are changing — slowly. We need more scripts where love feels equal, age is real, and desire doesn’t only belong to the 20-year-olds.”She urges filmmakers to flip the script and embrace mature storytelling: “Women definitely look better as they age because they take care of themselves. Compare a 50-year-old Indian woman to a 50-year-old Indian man — who’s sexier? Men don’t take care of themselves as much as women do.” Her candour challenges the twin biases of ageism and sexism head-on.Veteran perspective: Anant Mahadevan on skewed pairings

Director Anant Mahadevan points out the long-standing double standard. “The fixation on pairing has been a recurring issue for decades. An ageing male lead is no deterrent for filmmakers or audiences. We’ve seen 30-plus, even 40-plus, actors playing college students. But the lens isn’t as kind to female leads — marriage alone can lead to their declassification, let alone aging. It’s a myopic view of filmmaking.”He contrasts this with the West: “In Hollywood, female leads age with grace and are entrusted with mature characters. Here, we seem to doubt the appeal of our female talent. It’s just one of many clichéd ways we look at storytelling.”Breaking the mold: Rahul Bhat on chemistry and connection

Actor Rahul Bhat rejects the notion that romance is the domain of the young. Asked if he’d be comfortable playing a romantic lead opposite an older or same-age actor, he responds, “Absolutely. I think chemistry isn’t defined by age — it’s defined by connection, energy, and truthfulness in performance. We rarely see it because the industry has long fed into a one-sided fantasy: that men can age but women must remain frozen in time. That narrative is being challenged now, thankfully, but we have a long way to go.”He’s clear on the need for equity in storytelling. “Older actresses not only deserve to lead love stories — they need to. Love doesn’t expire at 35. In fact, it deepens. Women who have lived, loved, lost, and evolved have far more textured stories to tell. Why should those stories be denied a romantic arc?”On portraying love across an age gap, he adds, “It depends on how the story handles it. If the age gap is there to titillate or pander, it feels forced. But if it’s honest and rooted in character, it can be incredibly moving. As actors, our job is to find that emotional truth — age should add layers, not limitations.”He also calls out the industry’s long-standing bias: “Scripts have long equated desirability with youth. But the good news is, that’s changing. Actresses like Vidya Balan, Konkona Sen Sharma, Shefali Shah, Neena Gupta — they’re leading love stories with incredible grace and depth. Audiences are responding. The industry just needs to catch up.”Sadia Khateeb: Acting transcends age

Sadia Khateeb, who starred in The Diplomat, shares a grounded perspective: “I mean, as long as actors are comfortable being paired opposite each other, it does not matter if the girl is older or vice versa. Acting is a job where one has to act; it has nothing to do with realism.”She emphasizes that casting choices should serve the story and the director’s vision: “If the director has a vision and the script demands such a pairing, then as actors, we have to fulfill that vision and make the story work.”However, Sadia also calls out the pressures women face: “I hope seeing ageing of women as an expiry date changes over time; it’s a deeply rooted stereotype that has been ongoing not just in the industry, but in society. Women, after they cross a certain age, have a lot of pressure. Age shaming women is somehow a conditioning that has happened over the years — a sort of patriarchy. I hope and pray this changes eventually. Ageing is beautiful; it means you are living.”Time to grow up: Sandiip Sikcand’s blunt take

Actor and creative director Sandiip Sikcand doesn’t mince words. “It’s ridiculous to see men in their 60s dancing with heroines old enough to be their daughters. Even audiences recognize the disconnect — that’s why these films live on hype and Instagram reels but flop at the box office.”He urges Bollywood to mature. “The same old stories, senior actors refusing to age, and talented women not getting the right roles — this all needs to change fast. More than stars or projects, Bollywood now needs stories and actors.”Sikcand points to global examples of progress. “In the West, women do their best work after 30. Even the South gives actors fabulous platforms — their finest work often comes when they act their age.”Power imbalances in casting: Rajesh Tailang weighs in

Actor Rajesh Tailang highlights the deeper problem. “Bollywood’s romantic pairings aren’t just about chemistry — they mirror the industry’s power imbalance. The more powerful the male star, the less expectation there is for him to play age-appropriate roles.”He shares a personal example: “Meanwhile, I’m cast as the father of actresses who are paired opposite heroes 3–4 years older than me.”Ego and culture: Karan Razdan’s perspective

Writer and actor Karan Razdan traces the issue to deep-seated beliefs. “There’s an old Indian saying — a man never gets old. And I think the industry takes that literally. Whether it’s Mumbai, Chennai, or elsewhere, the hero’s ego still needs validation through a younger heroine.”Signs of progress: Karan Singh Chhabra on shifting dynamics

Actor Karan Singh Chhabra notes that change is visible, especially on streaming platforms. “If you look at recent web series, Bhumi Pednekar — who is older than Ishaan Khatter — is romantically involved with him, and the story requires that.”He’s hopeful about the direction things are heading. “Young actress, older actor, older actress, younger actor, same-age pairings — everything’s being explored now. Times are changing, and the audience is evolving.”Beyond Bollywood: Mozez Singh on societal bias

Director Mozez Singh expands the lens. “This entire concept is ageist and misogynistic — and it must change. Unfortunately, it’s not just films. In real life too, an older woman with a younger man is still seen as odd. But the reverse is normal.”He reminds us that cinema is a mirror. “The problem is bigger than Bollywood. Films reflect society — and that’s where the real work must begin.”Conclusion: Time for a new love storyThe age-gap romance trope in Indian cinema isn’t just a casting quirk. It’s a reflection of deeper societal norms that favour male stardom and female youth. But voices across the industry — from actors to directors and writers — are now challenging the status quo. The appetite for real, nuanced, and inclusive love stories is growing. And slowly, but surely, the script is beginning to flip.